I have thrown around the term "Old School" on this blog several times and thought it might be useful to explain how I personally define the term in reference to tabletop role-playing games.

If you think about it, the term "Old School" is a reactionary one (git offa ma lawn, danggumit!) and, unsurprisingly, different people react to be different things and in different ways. Moreover, in the role-playing game context, even things that were common "back in the day" weren't necessarily present at every gaming table. So, if you ask a dozen people what "Old School tabletop role-playing games" means to them, you will likely get a dozen different answers.

That's all well and good.

For purposes of this blog, in the role-playing game context, "Old School" refers to a type of gameplay that was common in the 1970s and 1980s and which I still use today at my table. Most notably:

Taking these one at a time:

When I write "GM rulings are emphasized over the Rules As Written," I don't necessarily mean a rules lite system or a game that allows the story to dominate play, rather than mechanics. Rather, I mean that the GM serves as "referee" or "judge" (to resurrect a couple more traditional terms), to make fair and impartial decisions.

Sometimes the GM makes a judgment call when there is a gap or an ambiguity in the rules, as sometimes is the case with older editions of Dungeons & Dragons. However, sometimes that also means he ignores or overrules the Rules As Written.

However, in many newer games, I find that the emphasis is on what the character can do, particularly in systems with lengthy character generation. For example, how I approach games like Pathfinder and Exalted is different (e.g., often my first instinct is to look at the character sheet to see what I have that might be applicable to a situation).

- GM rulings are emphasized over the Rules As Written

- Player Skill is emphasized over Character Skill

- Combat as War is emphasized over Combat as Sport

- GM rulings are emphasized over the Rules As Written

Sometimes the GM makes a judgment call when there is a gap or an ambiguity in the rules, as sometimes is the case with older editions of Dungeons & Dragons. However, sometimes that also means he ignores or overrules the Rules As Written.

- Player Skill is emphasized over Character Skill

However, in many newer games, I find that the emphasis is on what the character can do, particularly in systems with lengthy character generation. For example, how I approach games like Pathfinder and Exalted is different (e.g., often my first instinct is to look at the character sheet to see what I have that might be applicable to a situation).

- Combat as War is emphasized over Combat as Sport

By "Combat as War" and "Combat as Sport," I am referring to terminology developed several years ago to refer to differing play styles.

In the former, there's an "anything goes" mentality and individual encounters are not necessarily balanced or "fair". Rather, the GM presents a situation and the players decide what to do (combat is not a foregone conclusion).

In the latter, there are clear rules to encourage fair fights and an explicit goal for the GM is to present balanced encounters (combat is often a foregone conclusion). Sometimes, this is expressly baked into the rules set (e.g., newer editions of D&Ds' Challenge Rating (CR) and Difficulty Class (DC)).

A (in)famous type of Combat as War scenario is Fantasy F*ckin' Vietnam:

Another notable difference between the play styles is Combat as Sport, with its emphasis on balance, reflects the tendency of newer games to shy away from character death.

The possibility of character death, however, is a necessary baked in assumption of Combat as War. Indeed, this is an often overlooked an aspect of the play style (i.e., that war is dangerous, deadly and unpredictable). Combat as War is not just about planning and developing asymmetric advantages to stack a fight in your favor. Sometimes your best option is to run away or otherwise not fight at all (Of course, you have to have a GM that's not into railroading and willing to come up with new material on the fly).

Furthermore, there's an assumption in Old School play that bad things can and do happen to PCs. By this, I mean that, while the GM shouldn't be out to get the PCs or otherwise antagonistic, the players aren't going to have their hands held and the dice will fall where they may.

In the former, there's an "anything goes" mentality and individual encounters are not necessarily balanced or "fair". Rather, the GM presents a situation and the players decide what to do (combat is not a foregone conclusion).

In the latter, there are clear rules to encourage fair fights and an explicit goal for the GM is to present balanced encounters (combat is often a foregone conclusion). Sometimes, this is expressly baked into the rules set (e.g., newer editions of D&Ds' Challenge Rating (CR) and Difficulty Class (DC)).

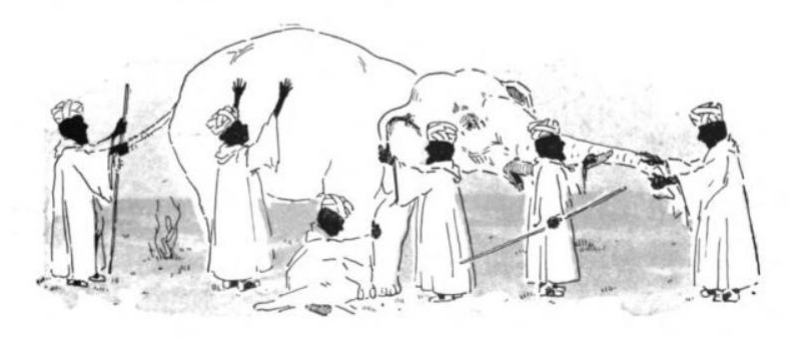

A (in)famous type of Combat as War scenario is Fantasy F*ckin' Vietnam:

[I]t was supposed to signify the dead-at-any-moment life of old school dungeoneering. The kind of play where you inched along the corridor, 10-foot pole in hand probing every foot of the floor, walls, and ceiling for traps. The kind of play where losing a limb prying open the lid of a chest was as quick as a death by an arrow from your flank. It was the gaming mirror of then still-fresh cultural memory of the stress, paranoia, and grittiness of the Vietnam War.

Another notable difference between the play styles is Combat as Sport, with its emphasis on balance, reflects the tendency of newer games to shy away from character death.

The possibility of character death, however, is a necessary baked in assumption of Combat as War. Indeed, this is an often overlooked an aspect of the play style (i.e., that war is dangerous, deadly and unpredictable). Combat as War is not just about planning and developing asymmetric advantages to stack a fight in your favor. Sometimes your best option is to run away or otherwise not fight at all (Of course, you have to have a GM that's not into railroading and willing to come up with new material on the fly).

Furthermore, there's an assumption in Old School play that bad things can and do happen to PCs. By this, I mean that, while the GM shouldn't be out to get the PCs or otherwise antagonistic, the players aren't going to have their hands held and the dice will fall where they may.

The prototypical examples of "Old School" RPGs are, of course, older editions of Dungeons & Dragons:

In fact, for some people, "Old School" = "older editions of Dungeons & Dragons" or "Old School" = "Old School Renaissance (OSR)".

However, personally, I take a more expansive view. The reason that I lump games like Traveller and GURPS with older editions of D&D into "Old School" is that my play style basically the same between them.

YMMV, of course.

No comments:

Post a Comment