Happy New Year!

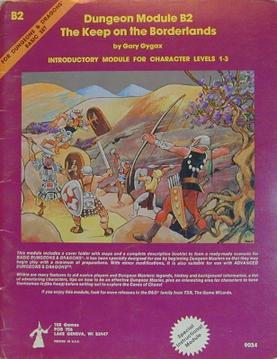

Recently, it came up in a conversation about how to start out as a

Game Master (or GM, for short) in tabletop role-playing. Being a GM is the most challenging and demanding position in any gaming group, so this week, I wanted to focus on some of the key issues that new GMs should consider.

First of all, before the game session even starts, beginning GMs should make sure that that their group's

Social Contract is in place, to match up everyone's expectations and to prevent easily avoidable problems.

Secondly, it is worthy to note that, with New School games, there are non-traditional ways to distribute the GM's role, including GM-less games such as Fiasco and Microscope and games using

Player-Facing Mechanics, such as Dungeon World. This post is not aimed at those games.

Anyway, in traditional tabletop role-playing games, being a GM entails wearing many "hats" (e.g., Author, Director, Referee, Manager, etc.) For example, as Referee, a GM must make judgement calls and decide when to apply

Rule Zero. Consequently, as one can imagine, there are many things to track and manage during a game session, but for beginning GMs, there three areas to focus on where one to get the most mileage:

- Prepare, Prepare, Prepare!

- Be Flexible

- Keep Learning

- Prepare, Prepare, Prepare!

Preparation, as with many things in life, can make all the difference when running a game session. As you become more experienced as a GM, you'll see more and more situations and learn how to juggle more and more things on the fly. However, when you're starting out, preparation goes a long way toward preventing problems and keeping things running smoothly. It will boost your confidence and speed up gameplay since you'll be less likely to struggle to fix things or figure things out.

A key part of preparation is knowing your rules set and the adventure that you have planned to the best of your ability. The more you've prepared, the faster you'll be able to identify and address potential issues, such as fielding your players' questions. It will also make it easier to address the next bullet point, Being Flexible.

In the words of the great German military strategist Helmuth von Moltke the Elder: “No battle plan survives contact with the enemy.” Similarly, your players may (*cough*probably will*cough*) do something unexpected that will fly in the face of all your hard work and preparation.

Don't panic. If you're caught off guard and need some time to figure out what to do, don't be afraid to call a bathroom break or even end the game session early.

And remember to keep an open mind. Particularly, don't worry about wasting a plot, a character, a setting or anything else you've spent hours to develop. In fact, you'll probably have a chance to reskin and recycle it later, with your players none the wiser.

Lastly, keep learning! Curiosity is a natural trait of the best GMs. You will get better with experience but there's always something that you can work on to become a better GM.

IMHO, one of the best things about being a GM is the opportunity to stretch your creative muscles, but muscles only get stronger with training and use. Talk to your players and other people- don't be afraid to solicit feedback and don't overreact to criticism.

Obviously, there are many, many, many other things to help start out as a GM and to become a better one, but if you begin with the above three areas, you'll have a head start!

.jpg)

.jpg/1280px-Role_playing_gamers_(III).jpg)