新年快乐! (Happy Chinese New Year!)

This week, I wanted to talk about one of the most important parts of a tabletop RPG's design: the Core Mechanic. By "Core Mechanic," I mean rules covering general task resolution (e.g., combat, investigation, negotiation, etc.) and reactions (e.g., surprise, morale, etc.), rather than related sub-systems (e.g., damage, initiative, etc.) or unrelated sub-systems (e.g., advancement, encumbrance, etc.).

Any discussion of Core Mechanics should begin with the ur-RPG, Original Dungeons & Dragons (1974). OD&D uses d20 target number roll under to determine hits in combat (the "Alternative Combat System" aka THAC0) and a collection of rules for reactions, such as d20 target number roll under (Saving Throws), d6 target number roll under (Surprise) and 2d6 look up (Monster Reactions). Additionally, as mentioned before, there are simply no rules for large areas of task resolution, with each table addressing this situation in their own way through house rules and/or role-play (for some, this is a feature rather than a bug).

These gaps, however, begin to be filled in with Supplement I: Greyhawk (Thieves Skills use d100 target number roll under and d6 target number roll under, Open Doors uses d6 target number roll under) and by AD&D, include many wonky rules, such as Chance to Know Spell.

Having so many disparate rules is a drag, both figuratively and literally, since they consume large amounts of the DM's bandwidth and/or slow down the game with multiple look up charts.

Unsurprisingly, while D&D was becoming more complex, a number of other Old School RPGs chose the opposite approach with more streamlined rule sets, such as Traveller (1977, mostly 2d6 target number roll over) and RuneQuest (1978, mostly d100 target number roll under). This more simplified design approach has won out, with most New School RPGs employing a universal Core Mechanic, most notably 3e and newer D&D (d20 target number roll over).

This week, I wanted to talk about one of the most important parts of a tabletop RPG's design: the Core Mechanic. By "Core Mechanic," I mean rules covering general task resolution (e.g., combat, investigation, negotiation, etc.) and reactions (e.g., surprise, morale, etc.), rather than related sub-systems (e.g., damage, initiative, etc.) or unrelated sub-systems (e.g., advancement, encumbrance, etc.).

|

| Not a core mechanic |

Any discussion of Core Mechanics should begin with the ur-RPG, Original Dungeons & Dragons (1974). OD&D uses d20 target number roll under to determine hits in combat (the "Alternative Combat System" aka THAC0) and a collection of rules for reactions, such as d20 target number roll under (Saving Throws), d6 target number roll under (Surprise) and 2d6 look up (Monster Reactions). Additionally, as mentioned before, there are simply no rules for large areas of task resolution, with each table addressing this situation in their own way through house rules and/or role-play (for some, this is a feature rather than a bug).

These gaps, however, begin to be filled in with Supplement I: Greyhawk (Thieves Skills use d100 target number roll under and d6 target number roll under, Open Doors uses d6 target number roll under) and by AD&D, include many wonky rules, such as Chance to Know Spell.

Having so many disparate rules is a drag, both figuratively and literally, since they consume large amounts of the DM's bandwidth and/or slow down the game with multiple look up charts.

Unsurprisingly, while D&D was becoming more complex, a number of other Old School RPGs chose the opposite approach with more streamlined rule sets, such as Traveller (1977, mostly 2d6 target number roll over) and RuneQuest (1978, mostly d100 target number roll under). This more simplified design approach has won out, with most New School RPGs employing a universal Core Mechanic, most notably 3e and newer D&D (d20 target number roll over).

I've spent a fair bit of time grumbling about various aspects of New School RPGs, but this is one area that I feel is a definite improvement than back in the Ye Goode Olde Days. By streamlining the Core Mechanic (and often other parts of the rules set as well), gameplay speeds up and GMs can focus on more rewarding parts of the game.

For Sorcery & Steel, my rules set, I've adopted a universal Core Mechanic (d20 target number roll under) to steamline play while not stepping too far away from its Old School D&D roots (descending AC). While starting as a set of AD&D house rules, Sorcery & Steel has become its own thing. However, I want to keep its DNA recognizable while fulfilling my other design goals.

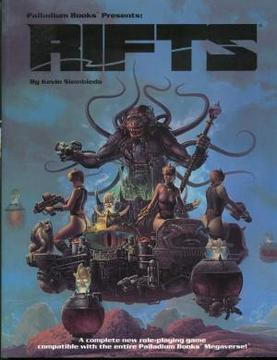

|

| ...and we liked it! |

For Sorcery & Steel, my rules set, I've adopted a universal Core Mechanic (d20 target number roll under) to steamline play while not stepping too far away from its Old School D&D roots (descending AC). While starting as a set of AD&D house rules, Sorcery & Steel has become its own thing. However, I want to keep its DNA recognizable while fulfilling my other design goals.