This week, I wanted to give a shout out to a legendary game that is both one of the pioneers of interactive fiction AND that also ranks as one of the greatest computer games ever!

A seminal computer game, in Zork, the player takes a nameless but intrepid adventurer down into the twisty and confusing realm of the Great Underground Empire in search of loot. Sound familiar?

Zork allows someone to singlehandedly play an Old School Dungeons & Dragons-esque text adventure. Unsurprisingly, winning requires using your head and a bit of luck to overcome terrible monsters and difficult puzzles. Roughly contemporaneous with the Choose Your Own Adventure (CYOA) gamebooks, this game was also an amazing and groundbreaking piece of interactive fiction that created its own genre. As with CYOA, Zork is written from a second-person point of view, in present tense, creating an inherent role-playing element.

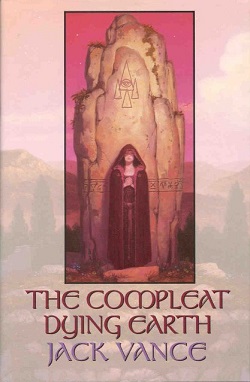

Aside from the clear influence of Dungeons & Dragons, there's also hints of Tolkien (e.g., the elvish sword that glows when danger is nearby), Jack Vance and classical mythology. While there were no graphics, Zork's minimal yet intelligent and witty prose brought the game to life with the power of the player's imagination, as with any good book (or tabletop RPG):

Zork (an MIT nonsense word that's slang for an unfinished program) was written between 1977 and 1979 by Tim Anderson, Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels, and Dave Lebling, members of the MIT Dynamic Modelling Group. Inspired by Colossal Cave Adventure (1976), the first adventure computer game, and using the same conversational and humorous tone and dungeon crawling format, Zork was a significant step forward in terms of technology, story and gameplay.

The game proved hugely popular over ARPANET (the precursor to the Internet) and a professor encouraged the co-authors to offer the game to the general public. The original program was so large that it was split into three games for the commercial release: Zork I: The Great Underground Empire, Zork II: The Wizard of Frobozz, and Zork III: The Dungeon Master.

The Zork series went on to become some of the top selling computer games of the 1980s!

Without mincing words, Zork is quintessential Old School: a challenging game, there's no hand holding and the player needs to use their brains and to carefully read the text to spot clues. One wrong move can produce an instadeath. Old School!

In addition, the terrain is complex and there is no automapping function- back in the day, you had to use paper to figure out by hand where the heck you were! Old School!

Moreover, just like an Old School RPG, there are no limits to what the player can attempt. Experimentation is implicitly encouraged and is sometimes the best path to finding the solution. Old School!

This game isn't for everyone but if you are looking for a classic dungeon crawler that will test your mind six ways to Sunday, "Zork" might be right for you.

Zork allows someone to singlehandedly play an Old School Dungeons & Dragons-esque text adventure. Unsurprisingly, winning requires using your head and a bit of luck to overcome terrible monsters and difficult puzzles. Roughly contemporaneous with the Choose Your Own Adventure (CYOA) gamebooks, this game was also an amazing and groundbreaking piece of interactive fiction that created its own genre. As with CYOA, Zork is written from a second-person point of view, in present tense, creating an inherent role-playing element.

Aside from the clear influence of Dungeons & Dragons, there's also hints of Tolkien (e.g., the elvish sword that glows when danger is nearby), Jack Vance and classical mythology. While there were no graphics, Zork's minimal yet intelligent and witty prose brought the game to life with the power of the player's imagination, as with any good book (or tabletop RPG):

Zork (an MIT nonsense word that's slang for an unfinished program) was written between 1977 and 1979 by Tim Anderson, Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels, and Dave Lebling, members of the MIT Dynamic Modelling Group. Inspired by Colossal Cave Adventure (1976), the first adventure computer game, and using the same conversational and humorous tone and dungeon crawling format, Zork was a significant step forward in terms of technology, story and gameplay.

The game proved hugely popular over ARPANET (the precursor to the Internet) and a professor encouraged the co-authors to offer the game to the general public. The original program was so large that it was split into three games for the commercial release: Zork I: The Great Underground Empire, Zork II: The Wizard of Frobozz, and Zork III: The Dungeon Master.

The Zork series went on to become some of the top selling computer games of the 1980s!

Without mincing words, Zork is quintessential Old School: a challenging game, there's no hand holding and the player needs to use their brains and to carefully read the text to spot clues. One wrong move can produce an instadeath. Old School!

In addition, the terrain is complex and there is no automapping function- back in the day, you had to use paper to figure out by hand where the heck you were! Old School!

Moreover, just like an Old School RPG, there are no limits to what the player can attempt. Experimentation is implicitly encouraged and is sometimes the best path to finding the solution. Old School!

This game isn't for everyone but if you are looking for a classic dungeon crawler that will test your mind six ways to Sunday, "Zork" might be right for you.