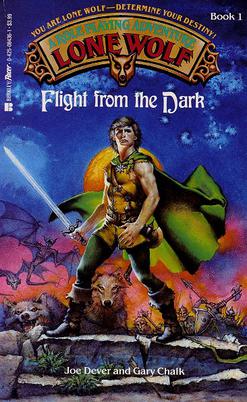

A couple months ago, I discussed the seminal Choose Your Own Adventure (CYOA) series of gamebooks. In the wake of CYOA's success and the concurrent success of tabletop role-playing (most notably Dungeons & Dragons), it is unsurprising that folks would start to blend the two, publishing gamebooks with light RPG mechanics. Today, I wanted to look at the first entry of one of the best of these hybrids, "Flight from the Dark" by Joe Dever:

In "Flight from the Dark," the reader plays the titular protagonist of the Lone Wolf series who, at this point, is an initiate and the sole survivor of the Kai monastery following a successful surprise attack by their archenemies, the Darklords. However, the Darklords have just gotten started and Lone Wolf must race against his enemies to reach the capital in time to warn the King of the impeding danger.

"Flight from the Dark" is the first book in the Lone Wolf series, which as of today has twenty-nine books. This probably makes the Lone Wolf series the oldest continuous gamebook, as well as perhaps the longest continuous novel with a single protagonist.

"While working in Los Angeles in 1977 [Joe Dever] discovered a then little-known game called ‘Dungeons & Dragons’. Although the game was in its infancy, Joe at once realised its huge potential and began designing his own role-playing games along similar conceptual lines. These first games were to form the basis of a fantasy world called Magnamund, which later became the setting for the Lone Wolf books."

There are two stats in Lone Wolf, Combat Skill and Hit Points... I mean "Endurance" Points:

Combat consists of comparing the opponents' Combat Skills, using a random number generator, and referencing the result on the appropriately named Combat Results Table. Rinse and repeat until Lone Wolf or his foe(s) are dead, hopefully the latter.

One can also see on the Action Chart above that the reader must select five of the Kai Disciplines in the first book. Not only does this provide customization and re-readability (i.e., a reader's play though can be different with each reading), but also a basis advancement, since the reader may add one additional Discipline after each of the first five books (the later books use a different but similar system). This also provides incentive to read the books in the correct order.

In terms of structure, the Lone Wolf books use a set of narrative bottlenecks, with a series of branching paths between each bottleneck. This structure works better with the light RPG mechanics than a purely narrative approach, since some paths may be more optimal for a particular PC than another one.

In also must be said that many of the books feature the excellent and distinctive artwork of Gary Chalk:

As a millennial gift, Messr Dever generously allowed Project Aon to publish the Lone Wolf books online for free! So, there's no excuse not to read them.